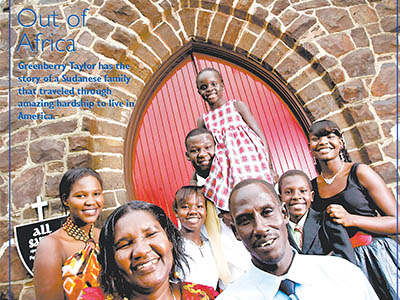

Out of Africa

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English.

Established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters

Running from death isn’t a realistic option, but it was the only one Ayen Kuot had.

Seated in the living room of her Midtown Mobile home, Ayen spoke to her 16-year-old daughter, Atong, telling her of their hard times in Sudan, Africa.

“The people came to take you and me and house,” Ayen said with a thick African accent. “They came to attack. Running was the only way to make life.”

“We saw a lot of bad things traveling,” Ayen said — now with four of her 10 children listening to her speak. “Very bad things.”

She told stories of lions eating people while they slept or when stopping to rest. Those who were sick with infections or lack of nutrition died along the way. Swimming across the Nile River, some were killed by hippopotamuses or crocodiles. Machine guns and landmines severed people’s limbs, or killed them. Death surrounded Ayen, but she kept her distance.

“Africa wasn’t always like this,” Ayen said sincerely. “Sudan wasn’t always like this.”

In May of ‘06, Ayen and her family stopped running — they had been cleared to come to the United States as refugees, Mobile being their destination. And while the family was extremely grateful, leaving their home in Sudan was difficult — but war is an ugly thing.

For over 20 years, the Second Sudanese Civil War has been active, making it one of the longest running conflicts in history. Beginning in the early ‘80s as a result of Sudan’s intent to become an Islamic state, troops from the northern region of Sudan started using violence and force in attempts to convert southern Sudanese to Islam.

Ayen, 44, was in her late teens/early twenties when the war began.

After receiving word about a scheduled attack on her small village in Ethiopia, Ayen left all her belongings and fled her home. Not knowing where she was headed, or if she’d ever see her family and friends again, she says she began walking across Africa, traveling up to 100 miles a day.

“There is no time when we walked,” Ayen said. “Just day and night.”

Water was so scarce along the journey, Ayen remembered picking up damp sand and sucking on it with the hope of getting just a small amount of liquid to quench her thirst. “A lot of people died. God took many of his people.”

Thomas, Ayen’s husband, went through similar struggles and is also no stranger to death.

“I served in the military (southern Sudan),” Thomas said. “A lot of war. A lot of sad things happen to my country.”

Cheating death on several occasions, Ayen finally made it to Kenya, where she and her family lived in a refugee camp for 12 years. This camp is where most of her children were born, except Abraham, Stephen and Manath.

“I remember being a little boy fishing everyday for our food,” Abraham, who is 30, said. “Fishing and tending to goats were my two jobs, until I was 7, this is when I was separated from my family and put into foster care.”

Abraham recalled hearing gunfire and running when he was a small child, fleeing from his village.

“I knew many people who were killed during war and as a result of it,” Abraham said. “War was all I knew since being born.”

Despite his siblings being born in a refugee camp, they also were witnesses to violence.

“Locals from around the area would come into the camp and start looting,” Atong said. “I can remember hearing gunfire and just running away from it. Afterwards, you would try and find your family members because everyone ran in different directions whenever attacks came. People were killed during these lootings.”

While living in the camp, Ayen and her children said they prayed everyday for the war to end. They also prayed to move to America. Both prayers were answered shortly after one another, the first being a cease in war.

On Jan. 9, 2005, the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (also referred to as Naivasha Agreement) was signed. The agreement was designed to end the civil war, develop democratic governance countrywide and share oil revenues. Not more than a year later, in 2006, the Kout family was granted their second wish.

“We came because of war,” Thomas, Ayen’s husband, said. “When the war stared in 1983, it scattered thousands of Sudanese all around the world. Four million to different countries. That is why we are here.”

American culture has had many differences for this Sudanese family.

Atong remembered the first incident her family had with American police.

“We were in a car accident and when the other driver said he was calling the police, many of us got out of the van and started to panic, some even cried. Everyone was very nervous,” she said.

Thomas explained that the police in Sudan weren’t known for being helpful, but rather for being abusive.

“Police usually beat a person to make them afraid of whatever mistake they made so they won’t do it again. People are afraid of the police,” he said.

When the police arrived, everyone was amazed they weren’t in trouble for being in an accident, according to Atong. “The police were concerned about our safety and well-being. This was so different from the police in Sudan. Mobile Police are very good.”

Abraham said another major cultural difference is the acceptance of change.

“If something new is introduced to culture, it is only kept if it has a positive impact and benefits the culture in some way,” Abrahah said. “If does not do either, it will not be adopted or practiced.”

Atem, 18 (the third oldest son), said education is much more valued here.

“Over in Sudan, only the rich can afford to go to school,” Atem said. “Here, everyone has the same opportunity and an emphasis is put on education.”

Atem is a recent graduate from Murphy High School, and plans on pursuing a college degree as well, just as his older siblings have done.

With 12 members in this family, one would think Mobilians might have met or seen the Kuots while out in public. Susie Pappas remembers the first time she met the family.

“I met Stephen (the oldest son) when I went into a carpet store here in town,” Pappas said. “I invited him to come to church and after he attended a few times, he started to bring more and more of his family members with him every service.”

Pappas is a member of All Saints Episcopal Church located on the corner of Government and Ann Streets.

It wasn’t long before the whole family began attending All Saints, including Ayen, who Pappas said might have been a little nervous to come since she spoke very little English. The more the family came, the more involved they became with the church and its members.

“As everyone got to know the family better, we started realizing there were things we could help them with,” Pappas said.

“When the Kuots first moved to Mobile in 2006, they were renting a small home on Government Street. The house, as it was described, was “horrible,” having a rat infestation and only two bedrooms to house a dozen people. Pappas said she remembers bunk beds in the living room and people sleeping on the couches.

With some help from All Saints, especially Associate Director Mary Roberts, the Kuots moved into a more suitable house for a family of their size. A clean, Habitat for Humanity home. Aside from helping the Kuots find another residence, members of the church also filled out paperwork for the children to enroll in school and volunteered to shuttle the family to English as a Second Language classes at Spring Hill College.

“In the years that they’ve been here, I feel like I’ve watched them grow so much,” Pappas said. “We have become such close friends, and they truly are the most welcoming and happy family I think I know. Despite everything they’ve been through, they truly believe in the American Dream; that anything is possible.”

This past July, the Kuot family took a 15-passenger van and drove seven hours to Nashville — the closest voting center for the Southern Sudan Referendum (SSR). The SSR will split southern Sudan from the northern region, forming its own country. Over 98 percent voted for this, and in less than a month, southern Sudan will be free from the oppression it has faced for over 20 years.

“I am very happy about this,” Abraham said as he watched a Sudanese news program with members of his family. “We have waited a long time for this. It is a good day.”

When asked, each member of the Kuot family said they planned on returning to Sudan someday.

“I want to take all of the knowledge I have learned and take it back to my people,”

Atem said with a gigantic smile on his face. “Yes, going home is something we will all do at some point,” Thomas said.

Since the Kuots have lived in the States for over five years, they can now apply to become American citizens, something they all plan on doing. Abraham even said some people have mistaken him for an Alabama native on some occasions.

Abraham started to laugh, and said he remembered a trip he took to Louisiana one time. He stopped at a gas station, and while paying inside, the attendant asked if he was from Alabama. With a thick Sudanese accent he replied, “Yes, I am from Alabama. But, how

did you know?”

“Your accent gave you away,” the attendant said with a serious tone in her voice. “Have a safe trip back to Alabama.”

The family couldn’t stop laughing. After all that they have been through, together, they are still laughing and still hopeful.

The original title of this story, as published in Lagniappe:African family runs from death and finds safety in Mobile. It originally appeared in the May 31, 2011, print edition.

Publication

Lagniappe